Does your workforce comply with safety requirements because they have to or because they want to? Some may think that as long as people are compliant, their motivation doesn’t matter. But, with 166 Australian workers still involved in a fatal work-related incident in 2019 and similar trends still occurring around the world, we can’t sit on our hands and pretend that ‘okay’ safety performance is acceptable. We must continue to make our workplaces safer and to do that we need mature mindsets.

Why is mindset so important?

At the heart of every safety incident is a person, and behind each person is the human brain. The brain is among many things responsible for making choices, focusing attention, allocating energy expenditure and observing hazards.

Every individual holds mindsets or attitudes towards safety, the organisation they work for, the task they are undertaking, their peers and so on. These attitudes direct their focus and drive behaviours that can be either helpful or hindering to their goal of remaining safe and well at work.

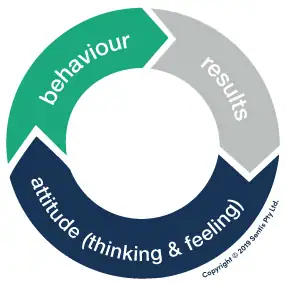

Different attitudes drive different behaviours when engaging with safety. In turn, these behaviours affect the level of risk being managed and the results for individuals’ safety. At Sentis, we use the Attitude-Behaviour-Results (ABR) Model to demonstrate the influence that our attitudes—what we think and feel—have on the behaviours we demonstrate and the results we see.

The ABR Model in action

Consider the following client example:

Two operators are scheduled to work in-field on the same pipeline. They experience the same incident, but with two very different outcomes. Both workers start their shift at the depot and engage in a prestart with their team and supervisor. Everyone is wearing their full PPE. Shortly after, they get to work in the field and are no longer being supervised. On the job, one of the workers (Worker A) decides to remove his gloves because they “get in the way of getting the job done.”

He claims he “can’t handle tools properly and no one is watching.” The other worker (Worker B) chooses to keep wearing his gloves for his own safety, and despite his best efforts can’t convince his co-worker to do the same. As they start working on the pipeline, an uncontrolled movement scrapes both workers’ hands. Worker A suffers a minor puncture injury to his hand; Worker B’s hand is protected because his gloves take the brunt of the damage. The worker who suffers the cut doesn’t think much of it and chooses not to follow procedure. He takes a “she’ll be right” approach and considers the injury a “normal” part of his job. However, the pipe is a breeding ground for bacteria, which is one of the reasons why gloves are required to be worn at all times. After three days, the worker starts to experience a fever and rapid breathing. He’s taken to hospital and diagnosed with sepsis—a potentially fatal condition most commonly caused by a bacterial infection— assumed to be caused by residual bacteria from the water present in the pipe. In this case, the worker was extremely fortunate and returned to work two months later.

Excerpt from Driving a Positive Safety Culture, 2019. Access the full report here.

Let’s consider the attitudes that Worker A held towards:

- Risk: “Nothing is likely to hurt me doing this task. Better to get the job done quickly.”

- Policies and procedures: “Wearing gloves all the way through this task is overkill.”

- Management: “There’s no point raising my concerns about the gloves to management – they don’t care anyway.”

- Colleagues: “What would they know?”

- Injury: “Its normal to get hurt doing this type of work”

- Reporting: “If I report, I’ll be raked over hot coals for not wearing my PPE.”

How did these attitudes drive Worker A’s behaviour? The worker operated without wearing the required PPE, ignored his colleague’s concern and didn’t report the injury once it occurred.

And what result did this behaviour achieve? A bacterial infection in Worker A’s hand and two months of time off work.

In contrast, Worker B chose to wear gloves and take ownership of his personal safety. He believed that safety came first (attitude), chose to follow the rules (behaviour) and returned home without injury (result).

Why do hindering attitudes towards safety exist?

How did Worker A end up with such hindering attitudes towards safety? Did he have an attitude problem?

Worker A is not too different from many of us. The brain develops hindering attitudes towards safety over time. It is unlikely that this was the first time Worker A had taken a shortcut to get the job done quicker. It may have started with Worker A considering it worthwhile to take a small shortcut when under production pressure. In that first instance, Worker A may have avoided injury and saved some time. His brain, which is hard-wired to conserve energy and seek reward, was then primed to take that shortcut again because the risks were perceived to be low and the benefits high.

It is likely that, over time, as Worker A took more risks and wasn’t injured, his hindering attitudes towards safety were reinforced. As a result, taking shortcuts gradually became the norm with saved time and energy the pay off—at least until an injury occurred.

If after this incident we asked Worker A why he got hurt and he said, “It was just bad luck,” we would likely see continued risk-taking behaviour and a higher chance of future injury.

The ABR cycle can be self-reinforcing and self-fulfilling. If Worker A believes safety is all about luck, he isn’t likely to start wearing gloves. However, if after the incident Worker A attributed the injury to his decision not to wear gloves, he may demonstrate greater safety responsibility in future. If his attitude shifted to “The gloves are here to protect my hands so I can throw a ball around with my kids on my days off,” then we are more likely to see Worker A wearing gloves in future and effectively protecting his hands and lifestyle with his family.

How do we change hindering attitudes towards safety?

The first thing we need is a powerful ‘why’. Change takes effort and we need to clearly see the benefits if we are going to change our thinking. Consider this… your team members only comply with safety procedures because they feel they have to and will get in trouble if they don’t. They don’t see value in the procedures and don’t want to follow them. How could you support your team to find a more powerful reason to engage in safety procedures?

First try exploring with your team the reasons why remaining safe and well at work is personally important to them. Have your team share with one another the things, people or future plans they want to protect by making safe choices. Then incorporate these reasons or the ‘why’ into the team’s safety vision. Making your safety vision and safety conversations more personal to workers is important because it provides the ‘why’ and supports them to shift their attitudes.

Safety leaders can also keep an eye out for workers demonstrating positive safety behaviours or communicating effectively about safety and reinforce both the behaviours and the helpful attitudes that drive them. For example, you could say, “Thanks for raising that safety concern. It shows that you’re concerned about keeping others safe on site too.”

Effective safety leaders are also skilled at asking questions to better understand worker motivations for compliance and non-compliance. When faced with non-compliance, these leaders use questions to challenge workers to think differently about safety. For example, “If that had gone wrong and you were involved in an incident, how would an injury like that affect you and those who care about you? What could you do differently to better protect yourself or your colleagues in future?”

Our brains resist change because it takes lots of energy and resources. Try to remember that when faced with workers who hold unhelpful attitudes, it isn’t easy for them to change the way they think about safety. However, if you can support them to see the reasons why they want to stay safe, you will start them on their journey to improved safety outcomes.

Changing safety attitudes in a workplace where there has been a long-standing culture of hindering or unhelpful attitudes towards safety may require a more holistic approach. A psychology-based safety training program can kick-start the culture change process and help your workers develop insight into the ABR model so they can take control of their mindset and their safety.